Shaping the landscapeGlaciers have influenced the character of a third of the Earth's land surface. Through their erosional processes, glaciers have produced probably the world's finest mountain scenery. The deposits laid down as glaciers recede are typically associated with a more subdued landscape, but these deposits commonly have a high commercial value, e.g. as a sand and gravel resource for the construction industry. Glacial erosion and deposition have produced a huge variety of landforms, many of which are illustrated in this section. |

The dramatic granite peaks of the Torres del Paine, tower above a moraine-dammed lake. A glacier filled the whole lake basin less than 200 years ago, and the only remnants occur on the intermediate bench above the lake and as a debris-covered calving mass at the foot of the cliff to the right. MH |  Crescent-shaped chattermarks and striations on bedrock of gabbro, Isle of Skye, Scotland. These features are the result of the juddering effect of debris-bearing ice as it slides over the bedrock. Ice flow was from top to bottom of the picture. MH |  Roches moutonnées were used widely in Scandinavia by bronze age people. The smooth rock surfaces were an ideal base for petroglyphs often showing people, boats and animals. This spectacular scene is near the south shore of Lake Mälaren east of Stockholm. JA |  Small-scale features of glacial erosion are striations (fine scratches) resulting from the abrasive characteristics of debris-laden ice sliding over bedrock. The whaleback form shown here is a roche moutonnée on Sandham in the Stockholm archipelago. It is abraded on the upstream side to the left and was plucked by ice on the right. JA |

Glacial abrasion (producing striae) and subglacial meltwater under high pressure give rise to channel-like structures (Nye channels) cut in the bedrock, as at the margin of Glacier de Tsanfleron, Switzerland. MH |  The erosion of a mountain from all sides by glaciers produce a ‘horn’ with steep arêtes rising to a sharp peak. Ama Dablam 6856 m) viewed from the Khumbu Valley is one of the world’s finest horns. MH |  The Lembert Dome in Yosemite National Park, California, is an exceptionally large roche moutonnée. It clearly demonstrates ice flow from right to left. MH |  A sunset over the Cordillera Huayhuash in Peru brings out the intricate detail of the arête on Nevado Jirishanca (6019 m). JA |

A series of cirques on the north flank of the Glyderau range in Snowdonia, Wales, viewed from Tryfan. The centre left peak is Y Garn (943 m), and the tarn below is Llyn Idwal. It was in the cirque containing this tarn that Charles Darwin recognised evidence of glaciation for the first time in Wales, in 1842. MH |  Lauterbrunnental in the Berner Oberland of Switzerland. This valley often regarded as a typical glaciated valley, in having a near U-shaped form in cross-section. True U-shapes such as this are relatively rare, however. The extremely steep valley sides causes numerous great waterfall, such as Staubbachfall seen here above the village of Lauterbrunnen. JA |  Glencoe in the Grampian Highlands of Scotland is one of the finest glaciated valleys in Britain. This view down-valley from ‘The Study’ illustrates the parabolic curved cross-section that is more typical of glaciated valleys than a U-shape. The crags on the left are known as the Three Sisters, and represent spurs truncated by the valley glacier. MH |  Near-vertical walls, eroded by glaciers, are characteristic of some glaciated valleys. Cathedral Rocks in Yosemite Valley, California are made up of an impressive a wall of granite. MH |

Glaciated valleys over-deepened below sea level are called fjords. Spectacular examples, exceeding over 100 km in length, are a feature of the coastline of East Greenland. Kejser Franz Josef Fjord is one of the longest, and over 1000 m deep in places. MH |  Mitre Peak (1692 m) is a horn located in the inner reaches of Milford Sound, a popular tourist destination in Fiordland National Park, New Zealand. This view seawards also illustrates a hanging valley to the left of the peak. MH |  Areal scouring is the product of powerful glacial erosion over relatively wide areas of subdued relief. This example shows ancient crystalline rocks (with black) dykes in the Vestfold Hills of East Antarctica, looking towards the ice sheet from near the coast. MH |  One of the best known glacial meltwater channels in Britain is Newtondale, cut by overflow from the ice-dammed Lake Eskdale. Meltwater incised this deep meandering channel as it flowed south (towards the top of the photograph) into glacial Lake Pickering during the last glaciation. The North York Moors Railway, which uses steam locomotives to carry tourists, follows this route. MH |

Erratic boulders, such as this north of Zug on the Swiss Plateau, transported by the ice age Reussgletscher, were first used by scientists such as Louis Agassiz in the early 19th Century to hypothesise that glaciers were once much more extensive. JA |  The lower slopes of Val d’Hèrens in Canton Valais, Switzerland are draped with thick deposits of ‘till’ – sediment released directly from a glacier. Near the village of Euseigne erosion of the till has left these well-consolidated pinnacles, capped by boulders. MH |  Till exposed in a roadside quarry above the north shore of Loch Torridon in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland. The texture is clearly visible with large boulders ranging down to clay-size material. The reddish colour is from the ancient sandstones that are a feature of this region. MH |  Although the deposits released by a glacier (till) have a wide mixture of particle sizes, meltwater streams rework and sort this sediment, producing sand and gravel. This example of sand at Bank-y-Warren near Cardigan, Wales shows faults that were generated as ice around the deposit melted. MH |

Glaciers carry large amounts of mud that is also removed by meltwater streams, and then collects in hollows. When it dries out, desiccation cracks form, as here near Kongsvegen in NW Spitsbergen. The polar bear footprints (about 30 cm diameter) give the scale. We met the culprit about half an hour later. MH |  When glaciers advance they push large amounts of debris before them. Then, as they recede, large ridges or moraines of loose debris are left behind. In this example, lateral moraines join with a terminal moraine to enclose a lake in front of Imja Glacier in the Khumbu Himal, Nepal. The collapse of such moraines is of concern because of the potential for lake-outburst floods. MH |  Twelve thousand year-old hummocky moraines in Coire a’ Cheud Cnoic (Corrie of a hundred hills), Glen Torridon, NW Scotland are amongst the best preserved glacial depositional features in Great Britain. Ice flow was from top right to mid-left. The small white cottage in front of the moraines gives the scale. MH |  Matanuska Glacier in Alaska contrasts strongly with the grey debris in front of it. Remnants of glacier become buried by debris, and as the ice slowly melts, small hollows called kettle holes form, filling with ponds. Vegetation is rapidly taking hold on the mineral-rich sediment in the proglacial area of this glacier and will soon become dense forest. MH |

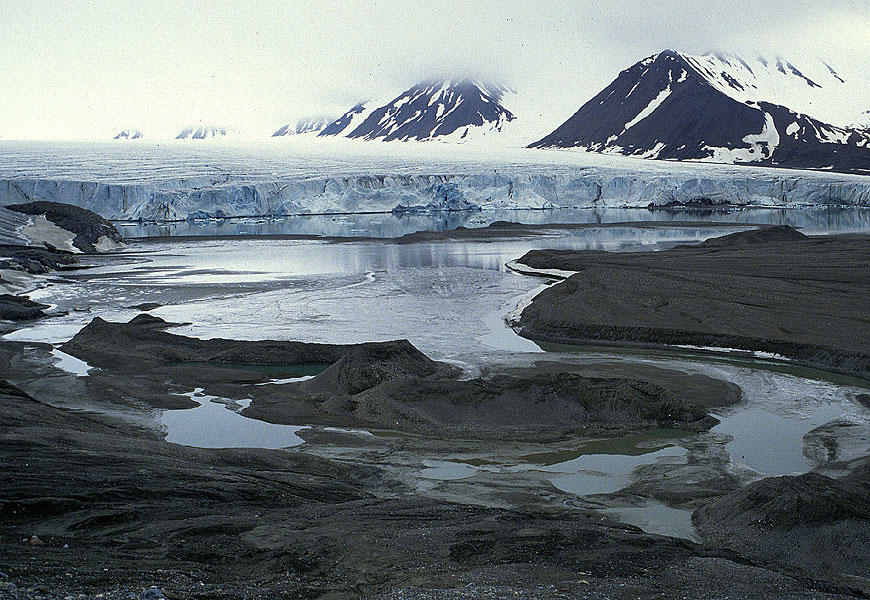

Meltwater commonly flows in channels beneath glaciers. They cut upwards into the ice, and then may become clogged with fluvial sediment. When the ice recedes an upstanding, sinuous, flat-topped ridge of sand and gravel may be left behind. This example is at the tidewater glacier of Comfortlessbreen in NW Spitsbergen. MH |  Tasman River with Mount Cook in the background is a typical braided river, in this case emanating from the Mueller and Hooker glaciers to the left and the Tasman Glacier to the right. Braided river are characterised by massive variations in discharge, so channel switching is common, and vegetation has difficulty becoming established. MH | | |

| Photos: Michael Hambrey (MH), Jürg Alean (JA) |