Living and travelling on glaciersThis section illustrates the ways humans live on glaciers, ranging from camping to large field stations. It shows also the various modes of glacier travel and the accompanying dangers. There are also images of the principal means of transport to glaciers in remote regions, such as by ship and aircraft. The main focus is on research work in the polar regions. |

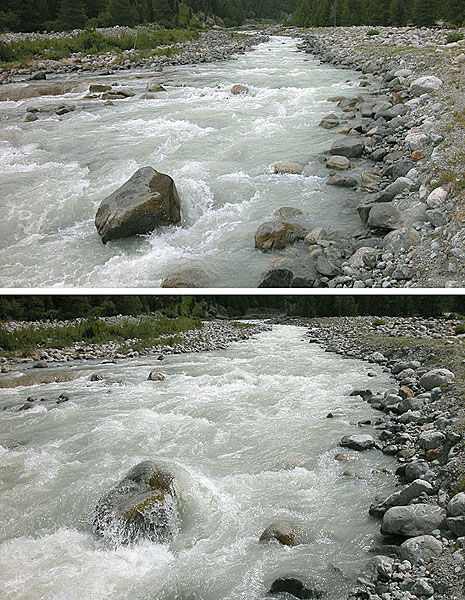

Camping on glaciers is one of life’s special attractions to an Antarctic scientist, despite its sometimes-arduous nature. Here, a geologist’s camp of the US Antarctic Program is set up on the lateral moraines of Shackleton glacier at 85º S. Traditional-style Scott pyramid tents are supplemented by modern lightweight mountaineering tents. Flags are used as markers in case of blizzards. MH |  Crevasses are one of the main obstacles to glacier travel. If they are visible, as this one on Griesgletscher, Canton Valais, Switzerland, then deviations from ones route are necessary. If they are bridged by snow, roping-up is necessary, and constant probing is necessary if one is to avoid falling through a bridge. MH |  Meltstream on the surface of White Glacier, Axel Heiberg Island, Canadian Arctic, beginning to emerge from the winter snow cover. Streams on Arctic glaciers can be several metres deep and be un-crossable, especially when the snow is beginning to melt and large areas of slush develop beneath the snow cover. The slush can sluice off down-glacier with little warning. MH |  Crossing glacial meltwater streams may be more difficult in the afternoon than in the morning due to changing amounts of discharge. The upper picture (visible only after clicking) was taken below Vadret da Morteratsch on a July morning, the lower in the afternoon after ablation and subsequent runoff had increased considerably. JA |

On the highland icefields of Spitsbergen, Norwegian Arctic, the weather can change suddenly. This storm approaching Wilsonbreen arrived within a few hours, and blizzard conditions subsequently prevailed for 3-days, confining the party in their tents. MH |  Walking on glaciers is fraught with many dangers, and roping up is usually necessary where the hazards are hidden. Here, during a training exercise, roped parties are crossing crevassed terrain on Ross Island. MH |  Cross-country skiing on Lomonosovfonna with a fibreglass ‘pulk’ (lightweight, boat-shaped sledge), a highland icefield in Spitsbergen. This is an efficient way of travelling over the undulating, snow-covered glaciers. MH |  A British Antarctic Survey dog-team on Adelaide Island, Antarctica. With the withdrawal of dogs from Antarctica under environmental regulations in the mid 1990s, travellers now have to rely on mechanised transport. (Courtesy of Nick Cox). |

The strongly-built Greenland husky was the mainstay of Antarctic dog-sledging. This animal, outside Scott Base in McMurdo Sound was a member of the last New Zealand dog team, shortly before its removal to New Zealand in 1987. MH |  For travel in small parties snow-scooters (‘skidoos’) are the ideal mode of transport over snow-covered glaciers. Here members of a geological party pause beneath 1500 m-high peaks during a 6-week summer-time traverse of the icefields of Ny Friesland in NE Spitsbergen. MH |  In mixed terrain of bare ground and snow-free glaciers, all-terrain vehicles have become popular. Here a geological party has just parked its Honda ATVs at camp at Hamilton Point on James Ross Island, just as a blizzard begins. Icebergs in Admiralty Sound can be seen through the driving snow. MH |  For carrying heavy equipment and large numbers of people in Antarctic tractor trains are commonly used. Here we see a Kiwi field party of the sea ice in front of Barnes Glacier cliff on Ross Island. This versatile Swedish-built tracked vehicle, a Hagglund, can even float if it breaks through the sea ice. MH |

At the top end of the mechanical transport spectrum is this huge comfortable bus, named ‘Ivan the Terrabus’, presumably after one of the Russian Tsars. It is used by the US Antarctic Program to ferry passengers to Williams Field, the runway on McMurdo Ice Shelf near Ross Island. MH |  Major scientific operations in Antarctica that involve ice drilling or co-ordinated geological projects require the installation of the equivalent of a small village. The US Antarctic Program relies on LC-130 ski-equipped ‘Hercules’ aircraft, as here in support of a geological programme on Shackleton Glacier in the Transantarctic Mountains. MH |  A UH-1N ‘Huey’ helicopter, operated by Antarctic Development Squadron Six, is typical of the support scientists receive for short journeys to field sites in the McMurdo Sound region. This aircraft is providing support during a stop-over at Taylor Glacier in the Dry Valleys. MH |  Camping equipment in Antarctica must be able to withstand hurricane-force winds. Pyramids are anchored down rocks, snow and supplies. Here we see a French-manufactured ‘Squirrel’ helicopter approaching a camp on Shackleton Glacier, Antarctica with a view to resupplying a US geological party. MH |

Only icebreakers can sail safely through iceberg-infested waters, and even then underwater iceberg projections (‘keels’) can pose a serious hazard. Here the Royal Navy icebreaker, HMS Endurance, is undertaking a hydrographic survey between James Ross Island and Snow Hill Island in the Antarctic Peninsula region, so maintaining a grid pattern of necessity entailed sailing close to clusters of icebergs. MH |  An unusual luxury for a British Antarctic Survey glaciological party in the ‘deep field’, several weeks into a field season, is a hot bath, improvised from a hot-water drilling system for measuring internal deformation of an ice stream. (Photo courtesy of David Vaughan). |  A geological field party camping in the accumulation area of Wilsonbreen, an outlet glacier in NE Spitsbergen, with the peak of Backlundtoppen (1081 m) in the background. Tents are secured by piling snow on the valences. The vehicle to the left is an all-terrain ‘Argocat’, fitted with snow tracks. The party had to be completely self-sufficient for a period of 6 weeks as it traversed this remote glacierised terrain. MH |  Major scientific programmes in Antarctica, away from the main bases, require complex logistical requirements. American operations are usually large-scale, as this geological expedition on the Shackleton Glacier in the central Transantarctic Mountains indicates. The camp was supplied by ski-equipped Hercules aircraft, with more local transport provided by two ‘Squirrel’ helicopters and a fixed-wing Twin Otter. MH |

Permanent stations on the Antarctic ice sheet have developed a variety of strategies to cope with snow accumulation, especially as snow drift tends to bury any object. The simplest approach is to use reinforced buildings and gradually allow them to be buried, such as Germany’s Georg von Neumayer station on the Ekstroem Ice Shelf. Living underground, however, is not the best way of experiencing Antarctica. MH | | | |

| Photos: Michael Hambrey (MH), Jürg Alean (JA) |